Preaching To The Choir, A Love Letter to Ridge Vineyards

Posted by Connor Smith on

I love making lists. Here’s a fun prompt: what are the greatest wineries in America?

I’ve got a lot of top 10 contenders turning over in my head, with emphasis on historical importance. All the ‘76 Judgement of Paris wineries. The 19th century titans Buena Vista, Inglenook, and Krug. The ultimate girl power winery and Prohibition-beater Simi. Andre Tchelischeff’s Beaulieu, and his disciples Mondavi, Grgich, and Heitz. The weirdos at Bonny Doon. The cult Cali folks, headlined by Screaming Eagle. Washington’s Chateau Ste. Michelle. Oregon’s Eyrie. One of these days I’ll sit down and hammer out an order.

But Ridge is my #1.

I’m not an impartial judge, as the terroir of my childhood was just down the hill from Monte Bello. But I don’t think it’s too much of a hot take. I’ve seen many a New York wine professional react to a Ridge mention with glassy-eyed flashbacks to bottles of yore, a small nod, and a “yeah they’re awesome”. It seems like a situation where there’s just not much to argue about. You might observe the same phenomenon with The Beatles, The Godfather, or Jerry Rice. It’s just so easy to taking something so perfect for granted. But we just hosted a seminar by the current winemaker up on Monte Bello, Eric Baugher, so it seems as good a time as any for us to look around and appreciate all that is good in life.

Monte Bello perched above a foggy Bay Area day.

Let’s run down the specs. Ridge sources from 15 vineyards as far north as Alexander Valley and as south as Paso Robles, almost exclusively old-vine red varieties such as Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Carignan, plus plenty less famous ones and a little Chardonnay to boot. They operate two wineries: the Lytton Springs estate in Healdsburg, and the flagship Monte Bello estate on Black Mountain, about 30 miles south of San Francisco overlooking Silicon Valley.

The iconic redwood facility at Monte Bello dates back to the 1880s, when vines were first planted on Black Mountain by an Italian doctor living in San Francisco.

With a scattered wine scene still putting back the pieces strewn about by Prohibition, the fateful day came in 1959 when a group of 4 Stanford scientists, led by David Bennion, joined together to purchase a vineyard for their personal use. So thrilled by the quarter-barrel of Cabernet produced in their first vintage, they decided to bond for commercial sale as Ridge Vineyards, and Bennion left Stanford to focus his efforts entirely on winemaking. In contrast to the U.C. Davis school of winemaking, Bennion valued old-world techniques, single-vineyard expressions, minimal chemical intervention in the vineyard, and a hands-off approach in the cellar. Perhaps not the philosophy you’d expect from someone who had been spending his days in a laboratory. Something special was clearly in the works, but the final ingredient to push it over the top proved to be a fifth partner added to the project in 1970, Paul Draper.

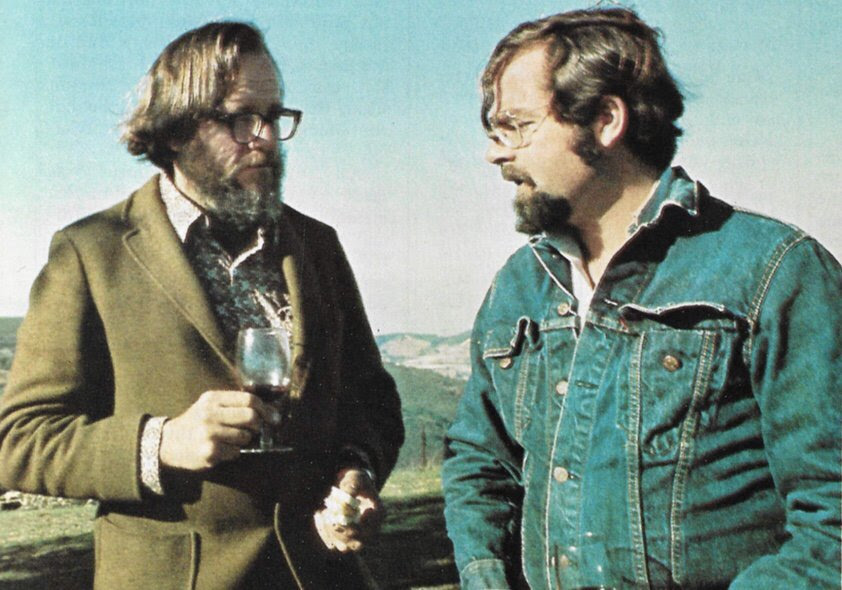

David Bennion (left) and Paul Draper (right).

Draper was a Stanford graduate in philosophy who had just returned to the U.S. after learning winemaking craft in Chile and Bordeaux, far from the influence of the bells and whistles that were forming the identities of Napa and Sonoma. Fitting like a glove into the philosophy of Ridge, Draper was also bringing along an entirely new level of vitilogical expertise. It was as if jet fuel had just been dropped in the engine. The very first vintage of Ridge Monte Bello by Draper’s hand, 1971, is one of the most legendary American wines of all time. It would compete at the 1976 Judgement of Paris, where it would place 5th among the reds. Always a wine that calls for aging, it has consistently climbed the board at subsequent re-tastings: 3rd in 1978, 2nd in 1986, 1st in 2006. Draper retired in 2016 after 47 years with Ridge, passing along responsibilities to three winemakers who have studied by his side for at least 20 years each: Eric Baugher, John Olney, and David Gates.

L-R: David Gates, Eric Baugher, Paul Draper, John Olney.

If you love American wine in general, there’s a lot to be grateful to Ridge in specific for. Old-vine Zinfandel, almost impossible to kill, had been languishing for decades as a blending grape or simply let to drop its fruit untended. Bennion was among the first to see it as having great potential to translate terroir, and Ridge’s bottlings in the 1960s can be seen as a watershed moment prior to the explosion of interest in Zin in the 1970s. Furthermore, Ridge was bottling their site-specific wines separately, and being as open as possible in regards to the vineyard location, grape blend, and alcohol content, all rarities in American wine at the time. When one considers the direction American fine wine is largely heading today - transparency, organic practices, single-vineyard bottlings, hands-off in the cellar, old vines - it is easy to look at Ridge as the predecessor and the flag-bearer leading their peers to this place.

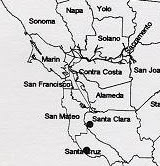

There’s one last pretty major point that must be made, in regards to the Monte Bello vineyard individually. In order to take a terroir-driven approach to great wine, you must start with great terroir. The San Andreas fault runs along the base of Monte Bello ridge, meaning everything to its west is part of the Pacific plate, moving southward. Some of these rocks, then, have been transported over millions of years from far afield in the Pacific. The fault moves offshore north of San Francisco, so you won’t get any of this effect to the north. Black Mountain specifically appears to have been an underwater seamount for a long time.

And you know what we get from land that used to be a sea floor? Limestone. This most coveted of winegrowing soils is everywhere in Burgundy, Champagne, the Loire, the Southern Rhone, the Bordeaux Right Bank, Rioja, and Jerez, but is conspicuously absent in Napa or Sonoma. And the Monte Bello vineyard sits on a whole big hunk of it.

Limestone deposits in the greater Bay Area. The one in Santa Cruz County is far too cold for grapes, the one in Santa Clara County is Black Mountain.

Conventional wisdom says that if you’re lucky enough to have some limestone, you’re practically morally obligated to stick some Pinot Noir in it. The other excellent Pinot estates in the neighborhood, such as Mount Eden and Rhys, are certainly doing wonderful things with their limestone deposits. And I’m sure Monte Bello Pinot would be lovely. But this incongruity surely plays a part in explaining why Monte Bello tastes so unique amongst Cabernets, normally considered a grape for gravel. And if making something exceptional in a way it’s not supposed to be done ain’t American, I don’t know what is.

Aftermath.

So that’s my take. Ridge is my #1. I’d love to hear your thoughts - think I’m underestimating one of the other great American estates? Is it a fool’s errand to even rank something like this - what does greatness really mean, anyway? Have a memory with a wonderful bottle of Ridge you’d like to share? I want to hear it!

Share this post

- 0 comment

- Tags: Cabernet Sauvignon, California, Monte Bello, Pantheon, Ridge, Santa Cruz Mountains, USA, Zinfandel